As you begin learning the violin, you might wonder, “why there are so many Italian words in my music?” And, the longer you learn and play written classical music, the more Italian music terms you’ll see!

It’s important to know what they all mean so you can play each piece of music the way it’s intended. Don’t worry about memorizing each and every term right away; you can download below a free booklet with all the terms, print it, and use it as a glossary when you come across new words in your music! (Or, you can bookmark this page 👍)

FREE List of Italian Music Words and Definitions

In this article, I’ll go through the Italian music terms we see the most in sheet music – especially in violin music – including dynamics, tempo, characteristics, and directions. So let’s talk about what these words are, their definitions, and why they’re there!

Table of content hideItalian composers were some of the first to write down music during the Renaissance era of music in the 1400s. They wanted to add more directions to achieve the desired sound. These composers began adding words in their language to their music to help guide players.

Italian music gained popularity throughout Europe, and, through the 19th century, most wealthy people who were able to learn music also learned other languages, including Italian. Therefore, they were able to read and understand the directions.

Now, fewer people may learn or know how to read Italian in addition to their native language, but the tradition of writing classical music with Italian terms has stuck. So now we learn those specific terms and follow them in our music.

Before we get into the terms you’ll see most often, I want to briefly talk about some small Italian words and parts of words that we’ll see often. It’s helpful to know these little connecting words and suffixes to fully understand what’s being asked of you.

“issimo” is a suffix (an ending to a word). This just means very or extremely, and is added to the end of a word to make it meaningful. “Very quiet” or “very loud” are two examples.

The Italian word “con” just means “with.” You might see a few phrases that use this word.

“Poco” means “little.” This is another word you might see as part of a longer phrase.

“Più” means “more”, and is used in a few musical directions.

The tempo of a piece of music is the speed: how fast, slow, or what character the composer would like you to play. We’ll organize our tempo terms from slow to fast.

In this section, I’ll mention bpm – this stands for beats per minute and is the number you can set a metronome to. If you’ve never heard of or used a metronome, I highly suggest reading about it on my online metronome page.

Grave is the slowest speed, and tells us to play at a slow and solemn tempo. The metronome marking for grave is 20-40 bpm.

Largo means “slow and broad.” A general metronome marking is 40-60 bpm.

Larghetto also roughly means “slow and broad,” but generally a little quicker than largo. We usually play this tempo around 60-66 bpm.

Adagio should be played slowly, with great expression, and at around 66-76 bpm.

Andante is generally referred to as a “walking pace.” It’s a moderately slow tempo. A good metronome range for Andante is 76-108 bpm.

Moderato, as you might guess, is just a moderate speed. 108-120 bpm will give you about that tempo! If you’re trying to find a moderato tempo without a metronome, try thinking of a marching pace.

Allegretto is just a little faster than moderato, but slightly slower than our next tempo, Allegro.

Allegro is a very popular marking, and it’s known as fast and lively, or sometimes quick and bright. A good metronome range would be 120-156 bpm.

Vivace is a fun tempo! It’s lively, fast, and brisk. You might find this in a lively piece.

Presto is a tempo that’s very fast. It’s rapid and brisk! A common metronome marking for presto is between 168 and 200 bpm.

Prestissimo is even slightly faster than presto! Anything above 200 bpm is considered prestissimo.

Italian words are also used for dynamics. Most dynamics are written with just a bold, italicized letter: the first letter of its name.

We’ll go from quietest to loudest, and then talk a bit about more nuanced dynamic terms.

of dynamic markings" width="720" height="1280" />

of dynamic markings" width="720" height="1280" />

Pianissimo is one of the quietest dynamics we can play. It’s a very, very soft piano; just a whisper of sound.

Piano is our quiet, or soft dynamic.

Mezzo piano is just a step above regular piano and is often referred to as moderately quiet.

Mezzo forte is moderately loud, not quite as big or heavy as forte.

Forte means loud!

Fortissimo is even louder than forte.

A crescendo can either be drawn under the music staff, or written out. It tells us to get loud gradually.

You might sometimes see a similar term, poco crescendo; this is just a smaller crescendo.

A decrescendo or diminuendo can also be written out or drawn underneath the staff. This tells us to gradually get quieter.

A sforzando tells us to play suddenly louder, on just the note marked sfz.

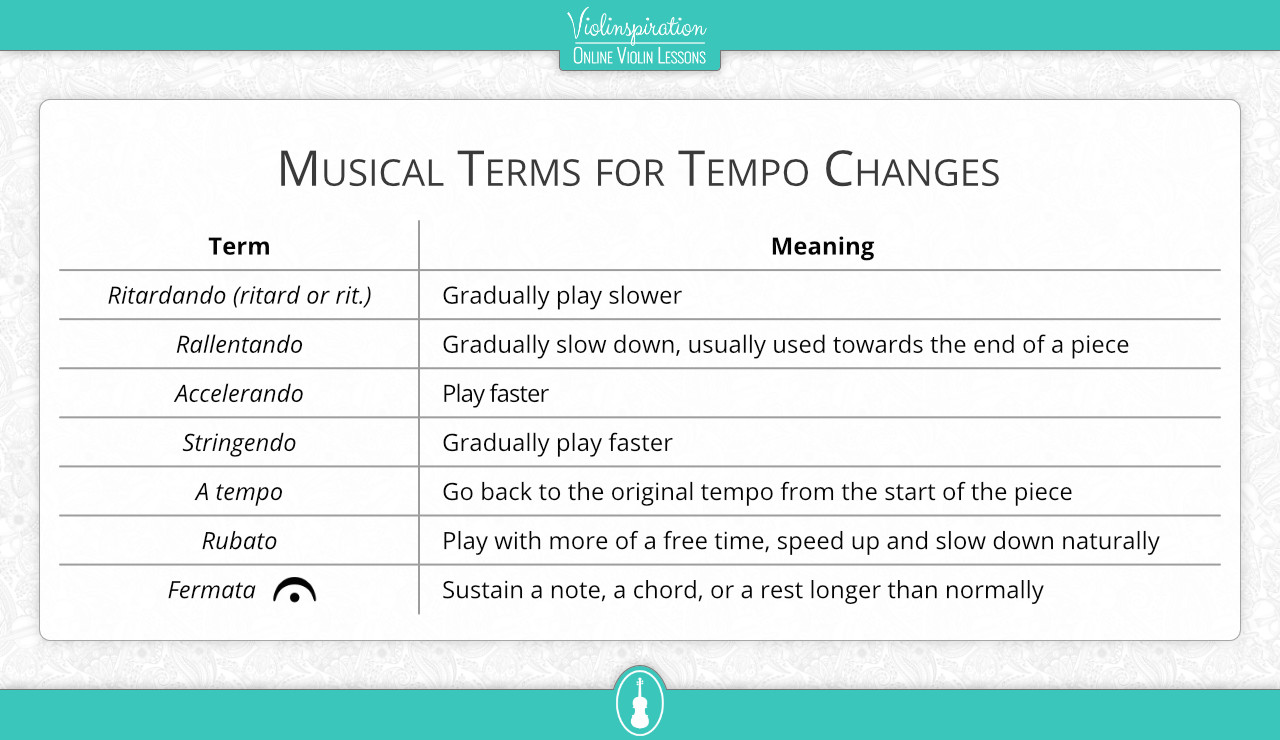

The tempo (the speed of the music) doesn’t always stay the same throughout an entire piece of music. Sometimes, we’ll see a direction to get slightly faster or slightly slower.

Ritardando (sometimes shortened to ritard or rit.) tells us to gradually get slower. This can happen anywhere within a musical composition.

Rallentando also means to gradually get slower, but I’ve found that this specific term is usually used towards the end of a piece, and therefore feels a little more final than a ritardando.

Accelerando is an Italian music term that tells us to get faster. You might see this in a really exciting section of music!

Stringendo is very similar to accelerando, in that it tells us to gradually play faster. However, stringendo literally means to tighten.

After a tempo change like ritardando, the composer might want the musician to go back to the original tempo from the start of the piece. In this case, they’ll write “a tempo” to indicate that.

The “a” at the beginning of the “a tempo” term is pronounced “ah” instead of “ay,” which can help differentiate between referring to the starting tempo, versus referring to any tempo.

The term rubato tells us to give and take time. Instead of playing with a strict tempo, we can play with more of a free time. Use musical expression to guide the speed of the music – it should speed up and slow down naturally.

When you see the fermata sign, you can sustain that note, chord, or a rest longer than you would normally play it.

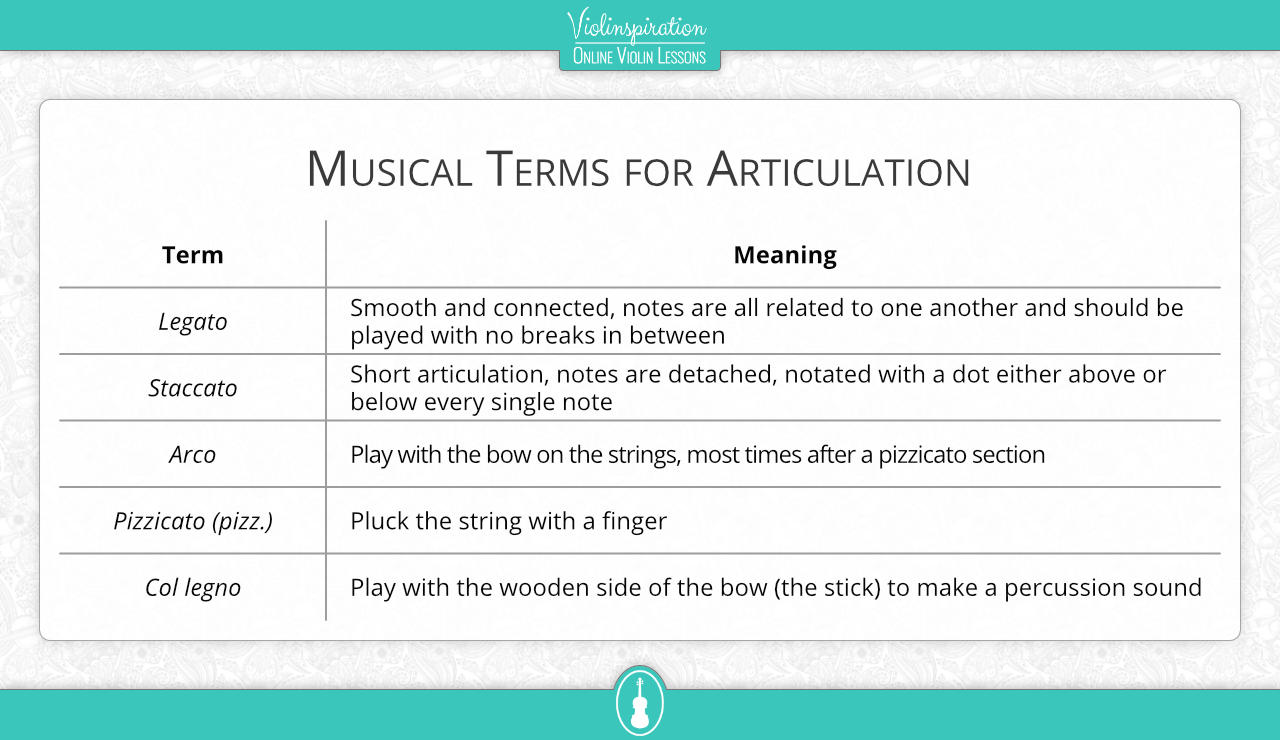

Articulation tells us what a specific note should sound like, and almost changes the texture of the note. Examples of different articulations would be short, disconnected notes, or, in contrast, a smooth connection between notes.

Legato is the Italian term for smooth and connected. These notes are all related to one another and should be played with no breaks in between. If a section of music is legato, you might see a lot of slurs.

Staccato is a short articulation, and notes are detached. It’s sometimes described as sharp or short. Staccato is notated with a dot either above or below every single note.

Arco means to play with the bow on the strings. This term is used almost exclusively for stringed instrument music.

Most violin songs should be assumed arco, although most pieces won’t explicitly say “arco” at the start. Most times, we’ll only see this term after a pizzicato section.

Pizzicato (shortened pizz.) tells us to pluck the string with a finger. When we see this marking, we’ll play every single note pizzicato until something tells us otherwise.

Here’s another string-specific Italian music term: the phrase “col legno” means to play with the wooden side of the bow (the stick). This is common mostly in orchestra music, and makes a very unique pitched percussion sound!